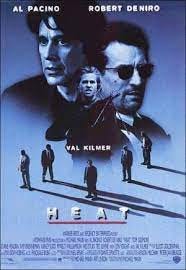

The 1995 film HEAT is a classic, but what about it makes it so powerful, so unique?

At the time of its release, it was marketed as the first time the two leads appeared opposite each other (they were both in GODFATHER II, but on different timelines. DeNiro played a younger version of Pacino’s father) and facing off.

However, they’d go on to costar in another film a few years later, another crime film that, sadly, few people saw. It wasn’t HEAT, let’s just say.

HEAT is a Michael Mann film, and he’s one of my favorite directors (and responsible for my all-time favorite film, in fact) and was born from real-life inspiration. There was a real Neil, a career criminal, and there was a real Vincent, and they did have coffee and discuss how it might all end (not good for the real-life version of Neil).

HEAT wasn’t even the first time Mann tried to tell this story, he did a version of it as a series called LA TAKEDOWN (check it out on youtube) that failed.

It failed on television, I suspect, more so because the story is an epic one and requires an epic vision (few big-screen TVs back in the early 90s) and palette.

Having seen it in the theatre, I can tell you that the entire audience was in awe, especially after the massive downtown shootout.

Much has been written about this film, and I’ll leave it to the reader to parse through… most of it is preaching to the choir… we know the great things about this movie, so no need to rehash everything… but watching it recently something new occurred to me that, in retrospect seems obvious, but I never caught onto it until now. It has to do with this scene and, in particular, this speech.

That moment, a classic, is actually the second time we hear it. Neil tells this story to Chris (Val Kilmer) earlier in the film. It’s his mantra, and it’s also why he has so little furniture. So the meaning of it is important.

I wrote earlier about how I like to define types of films (and again, it’s a broad general direction that serves as a starting point, not an ending point) structurally, and I find most films are three types (and they often have elements of each therein) to start with.

The First One is AGENTS OF CHANGE, which is about heroes who change the world, then we have AGENTS WHO CHANGE in part II, by far one of the most. common types of films in America, followed by AGENTS OF CHANGE III THE CHANGING WORLD which is how characters react to a changing world, a collision of worlds, so to speak.

What’s fascinating about HEAT is that it’s a pure colliding world (part III), a cops and robbers tale, but in this case, featuring TWO HEROES who are Agents of Change themselves. DeNiro robs armored trucks and banks. Pacino busts people who do that and both are excellent at what they do.

Which makes it a fascinating study, because we kind of root for both of them. They’re both fascinating, driven men doing things the rest of us only fantasize about.

And they are nearly exactly alike… what is unique about it is that the usual trope line where the villain tells the hero, “we not so different, you and I” isn’t spoken here, because both men simply recognize it in each other. It’s why the scene above is so very powerful… they are two men that, in different circumstances, would be friends.

So why does Pacino prevail over DeNiro? The lazy answer is because Pacino’s the cop and therefore the “hero” but it’s certainly not painted that way. In fact, the film starts with DeNiro, and DeNiro is painted with more compassion than his counterpart.

I’d suggest that while Pacino is more entertaining (she’s got a BIG ASS) DeNiro is far more empathetic as a character for us. We just like him so much more.

The reason DeNiro loses is that, from the get-go, he doesn’t take his own advice. He doesn’t walk away when he should and he doesn’t avoid attachments.

And this happens BEFORE THE FILM STARTS.

One might suggest that Amy, the girl he falls for, changes him, however, I do not think that is so. While he does fall for her, the character he’s most attached to is CHRIS. Chris ends up at his place when his wife kicks him out, DeNiro finds out Chris’s wife is cheating on him and confronts her FOR CHRIS, DeNiro cares about Chris for reasons that are never explained but definitely present.

Pacino is divorced multiple times and working on another… in fact, when he finds his wife cheating on him, he’s not surprised. He tells her, if it’s between you and the work, the work will win. He gives his wife and stepdaughter the bare minimum.

DeNiro knows the cops are shadowing them, and chooses the bank job anyway because he knows Chris needs the money. When the shootout goes down, DeNiro saves Chris (does nothing to help Tom Sizemore) and gets him to a doc (Chris would be the only survivor, in fact) and sets him up with an out.

Pacino’s men go down and Pacino barely bats an eye. He only has eyes on Neil.

DeNiro could get away, he has his out set, he’s even taking his girl with him this time, as Chris has done… but he cannot walk away from getting revenge on Waynegrow, the man who set them up. He gets his revenge, but it leads to his doom.

Pacino, on the other hand, is at the hospital because his stepdaughter tried to commit suicide and went to HIS PLACE to do it. He gets the beep and his wife tells him to go.

And Pacino DOES. Without a backward glance, he gets right back to it.

If he hadn’t adhered to the same policy, being willing to walk away from anything to do the job he loves… DeNiro would have gotten away. Pacino knew exactly where to look for him and found him.

Had DeNiro just left, just walked away from Amy, from Chris, he would have lived.

Had Pacino stayed with his wife, DeNiro would have gotten away even if he went after Waynegrow. That’s how good Neil was. Vincent was simply better and more devout to the philosophy that Neil preached, in the end.

I think that dance of characters, their colliding worlds, is what continues to fascinate me about this film. The characters don’t change (again, I posit DeNiro is attached to Chris from the get-go) and they’re on a collision course… and when it happens, the one who best embodies the philosophy wins.

I plan on discussing more Mann movies in the days to come, but this one, to me, is very nearly perfect, if perfection exists.

What do you think?